What a large meat company learned from protein entrepreneurs..

..or: alliance learning is as much about context as it is about transferable innovation content ‘secrets’ when it comes to sustainable innovation.

During a case study with a European meat producer and wholesaler [turnover $2.7bn in 2019/2020] we analyzed sustainability-specific learning processes and outcomes. The meat company –let’s call them BIGMEAT- formed 9 learning alliances with startups that operate in the food protein space. BIGMEAT wanted to explore food proteins other than animal-derived meat. The startup alliance partners offered ethical and ecological food tech innovations, including plant-based, insect-based, cell-based and 3D-printed meat analogues.

The study, conducted in Germany by Charlott Hübel with myself and Stefan Schaltegger, found that alliance learning for sustainability innovations has distinct characteristics. Previous research and conventional wisdom told us that large companies learn innovation content from smaller and more nimble alliance partners: this learning from is where large companies gain important innovation knowledge. This content has value to a firm outside the scope of the alliance, as the large company internalizes knowledge gained through the alliance to enhance their own operations. And then there’s the ‘cuddlier’ type of alliance learning: research defined this as partner-specific learning along the five dimensions of environment, goals, skills, task and process. This type of learning – called learning about- with supposedely little value outside of the alliance in question was thought to take place only at the early stage of new learning alliances. The later alliance stages were thought to be content learning [i.e. learning from] only. But in our study on BIGMEAT and its 9 learning alliances with protein startups, learning about took place in the later alliance stages also, sometimes with more prominence than the content learning. Learning about alliance partners is more significant than learning from in our study.

Why might this be?

Learning from can have a negative impact on alliances or even lead to earlier than planned alliance termination, when one partner “outlearns” the other content-wise and takes advantage of its increased bargaining power and starts using its acquired knowledge competitively. In alliances between large companies and startups, the large company is much more likely to win the learning race. To paraphrase: the big company can easily steal content knowledge from the smaller company and makes money from this knowledge. To learn anything about innovation content at all, however, requires that the large company can overcome learning challenges, for example, lack of management commitment or business-as-usual corporate structures. Research on interorganizational trust highlights that alliance partner familiarity and understanding is needed for any knowledge transfer to occur. Sustainability innovation is usually not part to business-as-usual corporate structures and BIGMEAT was no exception. This is where learning about comes in with its focus on business environment, company goals, skills, tasks and processes.

When choosing new alliance partners, learning about the partner was always thought to dominate during set-up and the starting phase of the learning alliance. In contrast, with the alliance up and running, learning from was increasingly thought to dominate. Yet, our study clearly found that for sustainability innovation, learning about was key even when the BIGMEAT learning alliances with food-tech startups where up and running. The learning about dimensions of environment and goals had a lasting impact on BIGMEAT management commitment. Now senior BIGMEAT employees integrated global sustainability concerns into decision-making. An employee recounts how the interaction with a startup founder gave him a new “awareness to find alternatives” at BIGMEAT and encouraged him to consider global food security concerns.

“These are perspectives that I have only adopted in the last few years because of such people and companies”.

Other BIGMEAT managers, after learning about the sustainability potential of the startups’ products, began to question the business-as-usual corporate structures and long-term viability of conventional meat production. They became more open toward food protein solutions other than animal meat. The food protein startups highly welcomed knowledge spillovers of sustainability perspectives and goals to BIGMEAT and saw BIGMEAT’s involvement in the alternative protein field as contributing to their own agenda of transforming the whole market toward sustainability. A startup founder, for instance, stated

“We are definitely an ideologically-driven startup. Maybe in other ways BIGMEAT wouldn’t have been exposed to the potential of the ideologically-driven activities we display in our business. I think in that sense we are affecting them. And through this, BIGMEAT is also exposed to the audiences that very much relate to this ideology. And BIGMEAT sees other potential value in that as well. I think it’s extremely beneficial for all sides.”

So, clearly, when it comes to sustainability innovation the content-focused learning from and alliance partner-specific learning about are both important – and not just for the large company, in our study BIGMEAT. It could even be argued that learning about and learning from merge when it comes to learning alliances that aim to further sustainability innovation.

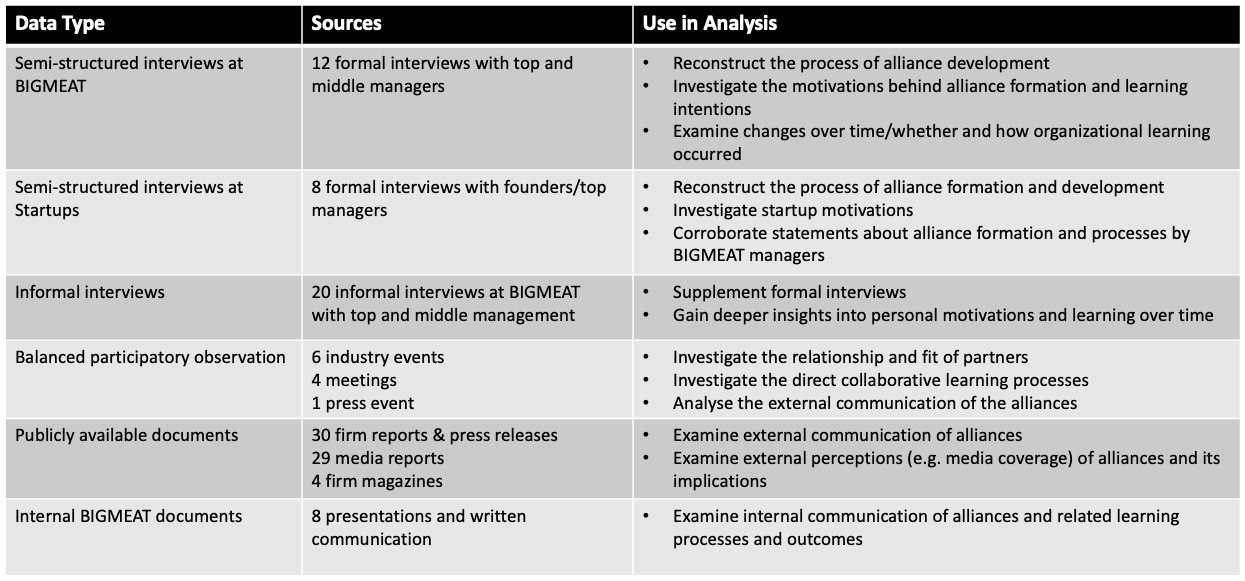

What did the BIGMEAT alliance learning study entail? 32 interviews with senior management at BIGMEAT over a period of 18 months formed the backbone of the study. 8 interviews with the founders/leadership of the alternative protein startups enabled reconstructing the process of alliance formation, development, and processes. Learning about and learning from alliances was systematically analysed for all learning alliances.

The full study is available open access in the academic strategic management journal Long Range Planning.